|

commercial grill on right. |

|

THE CLASS

One day I tried to explain what the SCA was to a coworker. I told her about my interests including researching period Mongolian dishes. The only question that she could manage to ask was "You mean, they didn't, like, eat large birds?" "Well, I guess but they mostly ate sheep," was the best I could explain. Then I came into possession of 'A Soup for the Qan.'

THE BOOK

'A Soup for the Qan' is a translation and study of a dietary manual called Yin-shan Cheng-yao (YSCY), meaning Proper and Essential Things for the Emperor's Food and Drink. An imperial court dietary physician named Hu Szu-hui wrote it during the Mongol, or Yuan, dynasty in 1330. Hu was primarily interested in medical aspects of nutrition; a central focus in the Chinese world, and the contents of YSCY reflects this. Most of the book is an account of the medical values of foods and recipes and how they affected ones' chi, or life force. The rest of the book gives detailed instructions on the preparation of court delicacies.

Medical aspects of the YSCY discuss the problems of the day in Mongolia and China. The text is concerned primarily with maintaining and regulating chi. It was believed that this could be accomplished through diet. This is done by avoiding contaminated, rotten, or suspect foodstuffs based upon cosmology, magical lore, folk beliefs, and accumulated wisdom from trial and error. Modern research shows that many of these choices are based upon empirically observed vitamin and mineral contents of food. The text indicates various activities that can lead to illness. It attempts to balance ying and yang, as well as emphasize following common sense. It warns that falling ill is due to excess.

The food and means of preparation discussed within 'A Soup for the Qan' are excellent gauges of social conditions, revealing cultural diffusion between various ethnic groups. These cultural spheres of influence on the Mongolian empire range across Asia especially from China and the Muslim world. Recipes and medicinal beliefs listed in YSCY can be traced back to many of these groups.

The Mongolian Empire at its height was so vast that it was broken down into four kingdoms known as khanates. The seat of power was in the Khanate of the Great Khan, which was the original empire of Cinggis Qan composing of Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, Korea, Burma, Vietnam and northern China. The Chagadaai Qanate, named after Cinggis' second son, included Uzbekistan, Tajikstan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Several Middle Eastern countries formed the Ilkhanate including Iraq, Iran, Afghanistan, Turkey, Syria and Armenia. The last of the khanates to eventually fall was founded by Cinggis' youngest son Batu Qan and included Russia, Ukraine, Georgia, Poland and Hungary. Such a broad empire would lead to incredible diversity in culture and diet.

Period Mongols enjoyed a large variety of food products, mostly from animals they herded or wild vegetables they gathered. They were also skilled diplomats and were able to obtain almost any thing they wanted through trade on the Silk Road. The YSCY lists many common food items in its third chapter or Chuan. These include many different grains, liquors, animal products, poultry, fish, fruits, vegetables, and spices. YSCY was, after all, a manual for a Mongolian Emperor in Chinese Court. Steppe Mongols typically did not eat fish unless they had to and pork and chicken were not commonly eaten either.

YSCY lists many diverse ingredients, as well as their medicinal values. Many items listed are the Asian variety, but often European foodstuffs were available too. Some grains listed include rice, several millets, soybean, chickpea, sesame seed, wheat and barley. Animals listed include ox, sheep, horse, elephant, camel, bear, donkey, deer, dog, pig, otter, tiger, leopard, rhinoceros, monkey, swan, goose, crane, chicken, duck, pigeon, dove, quail, and several varieties of fish. Fruits and vegetables eaten include peach, pear, plum, apple, orange, cherry, grape, walnut, lotus, ginkgo nut, olive, watermelon, acorn, parsley, mustard, onion, garlic, cucumber, radish, carrot, mushrooms, bamboo shoot, bokchoy, eggplant, basil, shallot, seaweed. Even though typical Mongol dishes are bland to western palates, they did have access to many spices including pepper, fennel, liquorice, coriander, ginger, tsaoko cardamom, turmeric, and poppy seeds.

THE TRADITIONAL DIET

One important note about 'Soup for the Qan' is that it describes the worldly delights prepared in the Yuan courts. The Mongols customarily ate what they could obtain from their flocks or by hunting or gathering. Dairy products were more popular in warmer weather when the livestock would foal and nurse, and meat more common in winter.

Mongols call these dairy products the "white foods." During that season they subsist almost completely on fresh milk, curds, sour milk, fermented milk, yogurt, and dried cheese from mares, cows, and camels. Mare's milk is four times higher in Vitamin C than cows' milk. This explains how Mongols could survive on a diet with minimal vegetables and fruit. They received iron and minerals from the underground wells where they retrieved their water. One advantage of meat during the winter is that it can be stored outside, frozen solid, until needed. The only concern is to keep it safe from dogs and wolves. The Mongols use wooden cages to keep the meat safe outside. If it is not cold enough to freeze the meat, it was made into sausages or dried so that it would have to be reconstituted later. This is part of the famous iron rations used by the invading Mongol army. '...They dry the flesh thereof by cutting it into thin slices and hanging it up against the sun and the wind. Presently dried without salt, and also without any evil smell.' 1

This form of dried meat is known as borts. It was a major source of meat during the long cold winters, but often supplemented with fresh meat from the hunt. The flocks were rarely slaughtered for food during the winter since a family needed several hundred sheep to survive and could not spare any for meat. In addition, at this time of year, slaughtered animals would not yield much usable meat, which was not worth risking the future prospects of the herd.

Hunting was not only a means so supplement the source of food, but also a major recreational activity, and practice for warfare since they used many similar tactics, called nerge. Animals hunted included deer, wild boar, marmot, antelope, wolves, foxes, bears, and a variety of fowl.

Another element to consider is the Mongol's limited fuel supply. Summer or winter, argal (dried cow dung) is the most available and abundant fuel. Even more so today, wood is scarce and rarely burned. '...They cook their meat, with fires made of the dung of oxen and horses.' '...There are many different kinds of dung, and each has a different name; argal is only used for cow droppings, not for others. Horse droppings are second best, sheep droppings are only used if necessary. Cow droppings are best, since they burn hotter and longer.' As a result of limited fuel, Mongols used the most efficient methods of cooking. Boiling, steaming, cutting their meat thin or mincing it to cook quickly. Also, river rocks can hold their heat for long periods of time. By placing them inside an animal carcass or inside a cooking pot, you can minimize the cooking time required. In modern Mongolia, hot rocks are placed inside sealed pots with meat, onion, and rice to create a pressure cooker effect. When pots were not available, the animal itself could be used as a cooking vessel. Rocks were heated to red hot and then placed inside the animal and then it was buried and dug up when ready. 2

As trade and conquest increased, access to more goods increased as well including grain based foods of every sort including breads, noodles, and alcoholic beverages. Despite tradition, Marco Polo did not bring pasta back from China to Italy. The durum flour (semolina) is a product of Middle Eastern crops, not Chinese and certainly not Mongolian. Pastas eaten in the Mongol Empire was made from other grains.

The cuisine would be considered simple, monotonous and bland by modern western standards, and probably to the wealthier Mongols as well since cooks were imported from around the region to prepare exotic foods for the court. The Mongol term for cook is ba'urci, and this person was responsible for court food, especially the meat. The term is from the Mongolian word for liver, ba'ur.

The preferred traditional method of cooking was to over boil the meat into a dish known as sülen. This was originally a broth but later evolved to a thick stew served at banquet. Thickeners such as chickpeas, rice, barley, or others were added to a spiced mutton stew. The sülen would be served as a soup or cooked dry.

The primary herd animal of the Mongols was the sheep. This was the focus of the Mongolian pastoral nomadism. This variety of sheep is relatively small, producing just enough meat to be conveniently eaten, shared or preserved in a short time although they were used more for a source of milk than meat. Sheep's milk could be used to make butter and cheese. The wool is of little values except to make felt. After the sheep, goat was the second most prevalent herd animal of the Mongols. It was particularly useful because it did not rely on grass alone for nourishment. However, this was also a disadvantage because they would often eat the small bushes and trees that the Mongols depended on for construction of gers or for other uses. They otherwise produced similar goods to the sheep.

Mongols also enjoyed the marmot, but caution was necessary since it is now believed to have been a vector of the Black Plague. Like most animals listed in YSCY, parts of the marmot have been assigned medicinal properties.

With out the horse, the Mongols could not live their pastoral nomadic lives or had any success in their military campaigns. It's service as a mount was also supplemented as a food source but only in times of need or at great feasts since a man's wealth was measured in horses (bayan means rich in horses). Besides being a source of milk for kumiss, horses could also be carefully bled to nourish their riders in times of shortage of liquid. Heroes were often described by what kinds of horse they rode, in a similar manner as how modern people refer to what type of car one drives. Camels replaced the horse as a mount in the more arid regions, and also served as long distance transport. They were not often used for meat, but their milk was used to make kumiss.

ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES

The alcoholic beverages available to the early Mongols included various kinds of kumiss made from mare and camel milk, and honey wine referred to as boal by William of Rubruck, a Francisian monk and Papal envoy in the 1250s. Kumiss is actually traditionally called airag in Mongolian. It is the preferred drink of summer and a prestige food since large flocks (up to 60 mares) were required to have a sufficient supply of milk to have the excess needed for a constant supply. Most Mongols did have access to kumiss in the form of qurit, a hard sun dried milk curd that was rehydrated to form a thin, fermented milk.

As their conquests continued, the Mongols also began drinking millet beer, grape wine, and a variety of liquors known as arqi, which is a strong usually distilled liquor from Arabic arajhi, and probably came to the Mongols via the Turks. These included fruit brandies and grain vodkas. By then, the Mongols could brew beverages in conventional stills as well as use freeze distillation to make more potent drinks.

At great festivals, the Mongols would engage in ritual drinking, often to a beat provided by the qan in which every one was obligated to partake. One also had to hold one's liquor since vomiting up drink was considered taboo.

EUROPEAN PERSPECIVES

'A Soup for the Qan' also adds the several quotes from European emissaries to the Mongolian empire at its height. These help us get a first hand perspective of what it was like to live and eat on the steppe. The difficult lifestyle and limited food has led to a waste-not-want-not attitude, and table manners were not important to them. These quotes are from John of Plano Carpini, a Papal envoy to the Mongols in the mid 1240s.

"And while Cinggis was returning from that country [of the Tatars] he lacked foodstuffs and they [the Mongols] suffered from great hunger. And on that occasion it happened that they found the fresh entrails of a beast. They took them and cooked them, discarding only the dung. And bearing them before Cinggis can, he ate the entrails with his men. And from this it was ordained by him that they should throw away neither blood, nor entrails nor nothing else from a beast which they ate, excepting the dung... It is considered a great sin among them if anything is allowed to be wasted from either food or drink. Thus they do not allow bones to be given to dogs unless the marrow has first been extracted.

"The land of the Tatars [Mongols] has abundant water and grass and is suitable for sheep and horses. Their way of life is only a matter of drinking mare's milk to assuage hunger and thirst. As a rule, the milk of one mare is enough to satisfy three persons. When they are on campaigns or at home they drink only mare's milk, or they can slaughter sheep for provisions. With the Tatar nation, whoever has one horse must have a sheep herd of 600 or 700. When they go campaigning in China, and their mutton provisions are exhausted, they shoot hares, deer, and wild pigs as their food... Recently they have taken inhabitants of China as slaves. These slaves must eat rice to be satisfied. For this reason they [the Tatars] seize rice and wheat and cook and eat congee in their stockades.

"Furthermore, they are the most unclean and filthy in their eating. They use neither tablecloths or napkins, nor do they have bread [to use as a plate], or pay attention to it, and scorn to eat it. They have not vegetables or even legumes; and nothing other than meat to eat, and they eat so little meat that other peoples could scarcely live from it. And further they eat all kinds of meats except for that of the mule, which is sterile, and this they do disgracefully and rapaciously. They lick their greasy fingers and wipe them dry on their boots. The great ones are wont to have little cloths with which they wipe their fingers carefully. They do not wash their hands before eating, nor their dishes afterward; and if perchance they wash them in meat broth, they put the dish they have washed back into the pot along with the meat. Otherwise they do not wash pots or spoons or utensils of any kind. They like horse meat more than any other meat. They even eat rats and dogs and dine on cats with great pleasure. They drink wine with great pleasure when they have it. They get drunk on mare's milk which they call koumiss, just as others get drunk on strong wine. And when they celebrate holidays and the festivals of their forefathers, they spend their time singing, or rather shrieking, and drinking in bouts; and as long as such drinking bouts last, they attend to no business and dispatch no envoys. This is what the brothers of the Order of Preaching Monks, sent to the Mongols by the Pope and staying in their camp, experienced continuously for six days. They eat human meat like lions; devouring it roasted on the fire and soaked with grease. And whenever they take someone contrary or hostile to themselves, they come together in one place to eat him in vengeance for the rebellion raised against them. Thy avidly suck his blood just like hellish vampires."

MODERN MISCONCEPTIONS

The Mongolian barbecue is a modern Chinese invention loosely based on Korean bulkogi, and is not Mongolian at all. The Mongolian grill restaurants perpetuate the story that Mongol warriors would gather around a fire at the end of the day of battle and cook their food on an overturned shield or helmet. Although it is documented that Mongolian solders were organized in small groups that shared a cooking pot, the food was probably boiled mutton and reconstituted milk. Along with Mongolian barbecue, the Mongolian hot pot is the most closely associated with Mongolia by most modern people. Thin slices of meat cook quickly in broth, and then the broth can be drunk separately. The fire pot, a tabletop fire chimney with a well around it for the broth, is related to the samovar (a hot water dispenser and teapot warmer combined). The Mongols delivered the samovar to the Russians and the Hot pot to the Chinese. Their simple brazier and pot eliminated the need for a specialized cooking utensil. 3

|

commercial grill on right. |

|

APPLICATIONS TO THE SCA

Several wars ago, I was sitting around a campfire discussing Mongolian cuisine in a small group including a vegetarian and a Mongol. The vegetarian asked, "So, what do Mongolian vegetarians eat?" Well, it took about half an hour of laughing before the Mongol could explain that there are no vegetarians in Mongolia. One just couldn't survive on the steppes with out meat. However, modern nutritional and social beliefs allow for varying degrees of vegetarian and other dietary beliefs.

When cooking a feast in the SCA we must allow for a great deal of food allergies, moral and religious beliefs, likes, dislikes, and of course, whims of the reigning royalty. I suggest using your discretion and keeping several things in mind. For starters, different areas allow more leeway with authenticity. Also if one keeps in mind that at the height of the Silk Road, one could get anything from anywhere. It was not uncommon for a high court dinner from the Yuan dynasty to include dishes from the Mongolian steppe, China, the Middle East, and elsewhere in Asia. When necessary, I prefer to substitute northern Chinese dishes especially Szechwan. Two of my favorite recipes to substitute are cold noodles in sesame sauce and meatless huushuur.

THE RECIPES

Cooking with the YSCY:

One should also realize that the recipes in YSCY seem vague because they assume basic cooking skills and only specifies what a good cook would not know. Much is left to the discretion of the chef, but important matters are given more careful instructions. This includes spice mixes, cooking time, and often quantities of ingredients. Included in this paper are several recipes from YSCY, with my redactions. The conversion from the weights and measures used in the book to this hand out are rough estimates at best, and in some cases the serving sizes have also been changed. Use your judgment and follow these recipes more as a suggestion than dogma.

[3.] Bal-po Soup (This is the name of a Western Indian Food) 5

It supplements the center, and brings down ch'i. It extends the diaphragm.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsako cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverize and remove the skins), Chinese radish.

Boil ingredients together and make a soup. Strain [broth. Cut up meat and Chinese radish and put aside]. Add to the soup [the] mutton cut up into sashuq [coin]-sized pieces, [the] cooked Chinese radish cut up into sashuq-sized pieces, 1 ch'ien of za'faran [saffron], 2 ch'ien of turmeric, 2 ch'ien of Black ["Iranian"] Pepper [27B], half a ch'ien of asafetida, coriander leaves. Evenly adjust flavors with a little salt. Eat over cooked aromatic non-glutinous rice. Add a little vinegar.

Redaction:

1 leg of lamb

5 tsako cardamoms

2 cans chickpeas

1 Chinese radish (daikon?)

1 tsp saffron

2 tsp each turmeric and black pepper

½ tsp asafetida (kasni)

Coriander leaves

Salt and rice wine vinegar to taste

Place the leg of lamb, cardamoms, chickpeas, and radish in a large stockpot. Cover with enough water. Boil until aromatic. Remove lamb and radish, cut into bite sized pieces (radish should be smaller so as not to overpower the lamb). Return lamb and radish to pot, add seasonings, adjust flavor. This will be ready when it has the consistence of a thick stew. Serve in a large bowl over basmati rice and add a splash of rice wine vinegar for extra flavor.

[23.] Yellow Soup 6

It supplements the center, and increases ch'i.

Mutton (leg; bone and cut up), tsako cardamoms (five), chickpeas (half a sheng; pulverize and remove the skins).

Boil ingredients together into a soup. Strain [broth]. Add two ho of cooked chickpeas, one sheng of aromatic non-glutinous rice [34A], and five carrots (cut up). Use 'meat pellets' [made from] the 'meat pill' of the rear hoof of a sheep, one [sheep's rib] (cut up into small, square pieces), three ch'ien of turmeric, five ch'ien of ground ginger, one ch'ien of za'faran, and coriander leaves. Adjust flavors with salt and vinegar.

Redaction:

1 leg of lamb

5 tsako cardamoms

2 cans chickpeas

2 lbs rice

1 tsp saffron

3 tsp turmeric

5 tsp ground ginger (fresh is best)

Coriander leaves

Salt and rice wine vinegar to taste

Place the leg of lamb, cardamoms, chickpeas and rice in a large stockpot. Cover with enough water. Boil until aromatic. Remove lamb and cut into bite sized pieces. Return lamb to pot, add seasonings, adjust flavor. This will be ready when it has the consistence of a thick stew. Serve in a large bowl.

[34.] *Chöppün Noodles 7

They supplement the center and increase the ch'i.

White flour (six chin; cut into fine vermicelli), mutton (two legs; cook When done, cut into strip qima [and stuff vermicelli]), one set each of sheep intestines and lungs (Cook. When done cut up.), eggs (five, fry into omelet. Cut into "streamers"), sprouting ginger (four liang), root and tuber of the Chinese Chive (half a chin), *möög [mushrooms] (four liang), oil rape leaf, smartweed shoots, safflower.

[37B] Use bouillon for the ingredients. Add one liang of black pepper, adjust flavors with salt and vinegar.

Redaction:

6 cups flour

2 legs of lamb

5 eggs

4 tsp fresh ginger

1 bunch of Chinese chive

1 cup mushrooms

Salt, pepper, vinegar to taste

Boil lamb in bouillon until cooked. Remove, and slice into thin strips. Make vermicelli with flour and stuff them with lamb. Make five-egg omelet and cut into strips. Stir fry chives, mushrooms, ginger then add eggs at last minute and pour over vermicelli.

[49.] [41A] Seu [Pomegranate] Soup (This is the name of a West Indian Food) 8

It treats deficiency chill of the primordial storehouse, chill pain of the abdomen, and aching pain along the spinal column.

Mutton (two legs, the head, and a set of hooves), tsako cardamoms (four), cinnamon (three liang), sprouting ginger (half a ch'ien), kasni (big as two chickpeas).

Boil ingredients into a soup using one telir of water. Pour unto a stone top cooking pot. Add a ch'ien of pomegranate fruits, two liang of black pepper, and a little salt. The pomegranate fruits should be baked using one cup of vegetable oil and a lump of asafetida the size of a garden pea. Roast [i.e., dry cook ingredients] until fine yellow in color, slightly black. Remove debris and oil in the soup. Strain clean. Use smoke produced from roasting chia-hsiang [operculum of Turbo cornutus and related spp], Chinese spikenard [Nardostachys chinensis], kasni, and butter to fumigate a jar. Seal up and store [the seu soup] as desired.

Redaction:

1 leg of lamb

4 tsako cardamoms

3 sticks cinnamon

1 tsp ground ginger (fresh is best)

½ tsp asafetida (kasni)

1 pomegranate

2 tsp black pepper

Butter (unsalted would be more period)

Salt to taste

Place lamb, cardamoms, ginger and cinnamon in a large stockpot. Cover with enough water. Boil until aromatic. Remove lamb and cut into bite sized pieces. Return lamb to pot, adjust flavor. Cut the pomegranate into quarters, sprinkle with vegetable oil and kasni, and roast until slightly yellow with black spots. Cut it up into pieces and add to soup. Add butter to soup too. This will be ready when it has the consistence of a thick stew. Serve in a large bowl.

[52.] [42A] Deboned Chicken Morsels 9

Fat chickens (ten; pluck; clean; cook and cut up. Debone as morsels), juice of sprouting ginger (one ho), onions (two liang; cut up), finely ground ginger (half a chin), finely ground Chinese flower pepper (four liang), [wheat] flower (two liang; make into vermicelli).

[For] the ingredients take the broth used to boil the chickens and fry [dry cook]. Add onions and vinegar. Adjust flavors with juice of sprouting ginger.

Redaction:

3 lbs boneless chicken breast

1 lb Chinese noodles, linguini or vermicelli.

2 stalks green onion

1 tsp ground ginger (fresh is best)

2 tsp black pepper

Salt and rice wine vinegar to taste

Boil pasta until al dente. Cut up chicken into morsels and sauté. Add green onion, ginger, pepper. Adjust flavor with salt and vinegar.

[78.] Roast Wild Goose (Roast Cormorant and Roast Duck are the same) 10

[47A] Wild goose (one; remove the feathers, bowels, and stomach and clean), sheep's stomach [and attached skin] (one; remove the hair; clean and use to wrap the wild goose), onions (two liang) finely ground coriander (one liang).

Use salt and flavor ingredients together [with the onions and ground coriander]. Put into the goose's stomach [put the goose into sheep's stomach] and roast.

Redaction:

1 whole goose (or duck)

1 bunch green onion

1 Tbls ground coriander

Clean the bird outside and in, then stuff with scallions and coriander. Seal cavity with butcher's twine. Place in sealable yet ovenproof bag, container, pressure cooker, etc. Roast at about 375 F until done (an hour or more?).

[91.] [49B] Poppy Seed Buns 11

White flour (five chin), cow's milk (two sheng), liquid butter (one chin), poppy seeds (one liang. Slightly roasted)

[For] ingredients use salt and a little soda and combine with the flour. Make the buns.

Redaction:

5 lbs All purpose flour

1 qt milk

1 cup liquid butter (ghee)

5 Tbls poppy seeds

1 tsp salt

1 tsp baking soda

Combine dry ingredients, and add wet ingredients. Roll into balls and bake until golden brown.

Other Recipes:

Huushuur (fried) or Booz (steamed) Meat Pastries

|

Ingredients:

For the filling: 2 lbs minced mutton or beef, with some fat included 1 lbs cooked rice 3 ½ teaspoons salt 1 onion, chopped 2 cloves garlic, crushed Soy sauce to taste (just a bit) For the dough: 4 ½ cups flour ½ teaspoon salt water to mix |

Huushuur on the bottom and Booz on the top. |

Directions:

Mix the dough ingredients together and knead into dough. Divide into smaller pieces and roll these into cylinders about ˝ inch in diameter. Cut the cylinders into 2 inch lengths. Take one length of dough and squash it into a circle. Roll it out until it is about 4 inches wide. Roll more at the edges than in the middle, so the dough is slightly thinner around the edges. Put 2-3 teaspoons of meat mixture onto one side of your circle, leaving a space around the edge. Fold the other side over, pinching the edge flat. Leave one corner open and squeeze out the air, then seal the corner. Fold the corner over and pinch again, then work around the edge folding and pinching into a twist pattern. Repeat the process with the rest of the filling and dough pieces.

Using ample cooking oil, heat the oil in a wok. Fry three or four pastries at a time for two minutes each side, until they are brown and the meat is cooked.

Exclude rice and steam the dumplings instead of frying them to make booz or substitute your favorite mushrooms instead of the lamb for a meatless filling.

Roast Lamb

| Ingredients:

1 boneless leg of lamb, fat trimmed 3 tablespoons crushed garlic 2 tablespoons soy sauce 2 tablespoons rice wine or dry sherry 1 tablespoon ground pepper 1 tablespoon grated ginger 2 teaspoons sesame oil several finely chopped green onions |

|

Directions:

Butterfly lamb then mix other ingredients together. Add cardamom, star anise, or hoisin sauce to marinade for additional flavor. Rub marinade inside and out side of lamb. Tie roast to form a log with butcher's twine. Cover and refrigerate for 4 to 6 hours.

Roast, uncovered, 25 to 30 minutes per pounds for rare (140(F) or 30 to 35 minutes per pound for medium (160(F). Let sit 15 minutes or so before carving.

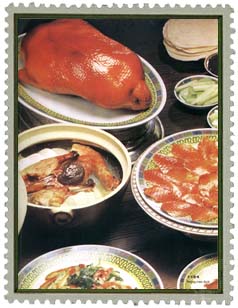

Peking Duck

| Ingredients:

7 lbs duck 5 cups hot water 3 tablespoons maltose 1 tablespoon vinegar 1 tablespoon sherry 1 tablespoon sesame oil 1 tablespoon sugar 1 tablespoon soy sauce 5 tablespoons hoisin sauce 12 Chinese pancakes, steamed ¼ lbs scallions cut into brushes |

|

Directions:

Clean a fresh duck and pump it full of air through the neck to separate the skin from the meat. (At home, a bicycle pump may be used.) Pour boiling water over the duck three times. Carefully dry duck, slit stomach, and remove innards. Prepare marinade of hot water, maltose, and vinegar. Rub outside of duck all over with the mixture. Hang the duck by its neck at room temperature, about 65 degrees, for at least 12 hours.

The next day, pre-heat oven to 400 degrees F. Place duck in pan and cook for 10 minutes. Turn heat to 450 degrees F and cook for additional 30 minutes or until the meat is tender and the skin is crispy.

To carve the duck, place it breast side up and cut downwards towards the head. Slice thinly. Use only the outer slices-those which have skin. Slice both breasts. Slice the legs, cutting from the joint to the end of the leg.

Combine the sherry, sesame oil, sugar, soy sauce, and hoisin Sauce. To assemble, place duck slices on pancakes. Use scallions to brush on hoisin sauce.

Hummus

Ingredients:

2 cans chick peas, set aside liquid

½ cup lemon juice

6 oz. tehini (Telma brand is my favorite)

2 to 3 cloves of garlic (or more)

1 to 3 tablespoons olive oil

salt and pepper to taste

Pita bread

Directions:

Chop garlic in food processor then add chick peas. Blend until chunky. Drizzle in olive oil, lemon juice and blend. Add tehini and blend until creamy. There should be small yet visible pieces of the chick peas. Add liquid from chick peas if the mix is too thick and season with salt and pepper to taste. Dip pita bread into mixture and enjoy. Or sprinkle a dash of hot sauce on first.

Cold Noodles in Sesame Paste

Ingredients:

1 lbs Chinese noodles, but linguine works well

5 heaping table spoons well mixed sesame paste (tehini)

4 tablespoons soy sauce

2 tablespoons honey

4 tablespoons sesame oil

1 tablespoon hot chili oil (or to taste)

1-2 scallions

1-2 tablespoons sesame seeds.

Directions:

Boil pasta, drain, run cold water over pasta to cool it while in colander. Lightly toss it with some sesame oil to prevent sticking. Mix other ingredients and remainder of sesame oil, preferably in blender. It should be somewhat thick, but runny enough to coat the noodles. Mix in cold water if it is too thick. Pour sauce over noodles, garnish with scallions and sesame seeds.

Suutei Tsai (Salty tea – suu means milk and tsai is tea)

Ingredients:

1 quart water

1 teaspoon salt (to taste)

1 tablespoon green tea

1 quart milk

Directions:

Boil the water, add tea and salt. Add the milk and boil again.

THE SCAdian FEAST

Although most of the previous recipes in this section are for period dishes, I do not have documentation for any of them, so I call them period-themed recipes. It is important to note that the pattern of the pinched edges of booz and huushuur is a matter of competition and pride. Several delicate forms can be made by the fingers, the smaller and thinner is the better for booz. The edges should not be very thin for the huushuur, because it burns when frying.

Peking duck is very similar to recipe [78] Roast Wild Goose (Roast Cormorant and Roast Duck are the same) in 'A Soup for the Qan' and quite probably is a more modern (though probably still period) version of the dish. The traditional method of eating this is to carve it into slices, which are eaten rolled in thin pancakes with a dish of hoisin and scallion, or cucumber cut in thin lengths. The remainder of the carcass would be used to make other dishes, and a creative chef can produce an "all-duck banquet" of over eighty dishes made of different parts of the fowl.

Hummus is a traditional Middle Eastern dish and one of my favorite snacks, as well as any other lover of garlic. It hails from the part of the Mongol empire known as the Ilkhanate. Cold noodles make a nice dish that's sure to please the crowd, but is not listed or documented as period. However, it is an excellent dish for vegetarians.

Kefir is a drinkable yogurt, which is easily found in most supermarkets or health food stores, and which can be documented to be period. Kumiss made from mare milk is obviously best. It can be a bit of an acquired taste and since it is alcoholic it won't be allowed on dry sites. Individual participants would have to BYOK (bring your own kumiss) since SCA corporate doesn't let us serve alcohol at events.

Suutei Tsai is actually more of a Tibetan recipe. To make a different type of tea, Mongolians sometimes also add a lump of rancid butter just before serving. This is called shar tos, or airag tos. Remember, if you hand someone a cup of tea (or anything else, for that matter) to always use your right hand only. Similarly, when accepting and drinking the tea, use your right hand. Serve in small bowls or cups.

THE BIBLIOGRAPHY

Books:

Buell, Paul D. A Soup For the Qan. Kegan Paul International, New York, 2000.

Buell, Paul D. Historical Dictionary of the Mongol World Empire. The Scarecrow Press, Inc., Lanham, Maryland, 2003.

Cramer, Marc. Imperial Mongolian Cooking. Hippocrine, New York, 2001.

Cleaves, Francis W., translator. The Secret History of the Mongols. Harvard Univ. Press, Cambridge, Mass, 1982.

Keys, John D., Food For The Emperor. Gramercy Publishing, New York, 1963

McCloskey, Mildred. The Complete Anachronist #54: The Mongols. SCA Office of the Registry, Milpitas, CA, 1997.

Web Sites:

A Dark Horde Family Album

http://www.greatdarkhorde.org/FamPics/

Food of the Mongols

compiled by Mark S. Harris aka THL Stefan li Rous

http://www.florilegium.org/files/FOOD-BY-REGION/fd-Mongols-msg.text

KEFIR.NET- The ancient antidote for modern maladies

http://www.kefir.net/

Meat, milk and Mongolia: Misunderstood and often maligned,

the Mongolian diet does make sense

by N. Oyunbayar

http://www.un-mongolia.mn/ger-mag/issue2/food.htm

Medieval Mongolian Cooking

by Crystal L. Smithwick aka Ynesen Ongge Xong Kerji-e

http://www.9v.com/crystal/kerij-e/docs/cooking.htm

Mongolia Asian Culture Page With Food Information and

Recipes from Asia

http://asiarecipe.com/monmain.html

Mongolian Barbecue

http://www.galaxylink.com.hk/~john/food/cooking/mongolian/mnbbq.htm

Mongolian Cuisine

http://ulaanbaatar.net/food/index.shtml

Mongolian Street Connection

http://mongolia.worldvision.org.nz/mongoliarecipes.html

OrientalFood.Com: Your Source for Asian Food and Culture

http://www.orientalfood.com

Roast Duck

based on material offered by Mr.Du Feibao

http://www.chinavista.com/experience/duck/duck.html

Silk Road Seattle - Traditional Culture: Food

http://depts.washington.edu/uwch/silkroad/culture/food/food.html

A Slaughter for A Feast

http://www.f8.com/FP/Russia/R07a.html

1

© 2002 - 2003, by Keith Mondschein, known in the SCA as Lord Aburga Chagatai

Send comments to avargachagadaai@aol.com

return to the Silver Horde home page.